Photo: Karl Hornfeldt / Unsplash.com

Theoretical background of Early Career Mobility

This section presents a summary of the literature review on the mobility behaviour of young adults, highlighting factors associated with migration trends and intensities. Previous studies emphasise the importance of understanding the mover's socio-economic background and residential history. Existing literature identifies several migration drivers which can serve as a framework for studying young adults' mobility behaviour and patterns. The literature review was conducted to support an effective survey design for data collection on migration history and migration aspirations of young people in the Nordic region.

The main schools of thought within migration literature have assumed that migration is largely driven by labour market conditions. The economic theory recognises the migrant as a rational actor seeking improved economic opportunities, such as higher wages and better employment conditions. As such, a decision to move is based on the calculation of the total benefit of moving versus the total cost of moving (see for example Sjaastad, 1962; Todaro, 1979). However, other schools of thought have highlighted the effect of personal characteristics on migration, arguing that the choice of migrating is not as rational as the economic theory presumes. Instead, migration and mobility patterns are influenced by a variety of factors, still including economic factors but also social networks and family ties, lifestyle preferences and lifecycle-course events such as graduation, marriage, having kids and divorce (Fischer & Malmberg, 2001; Lundgren, 2007).

There are several types of mobility behaviour among young adults, which often intersect and overlap with each other. These include, for example, educational, career, residential, temporary, lifestyle, social network, and international mobility. Connected to mobility behaviour is the reason for migration, often categorised as push and pull factors.

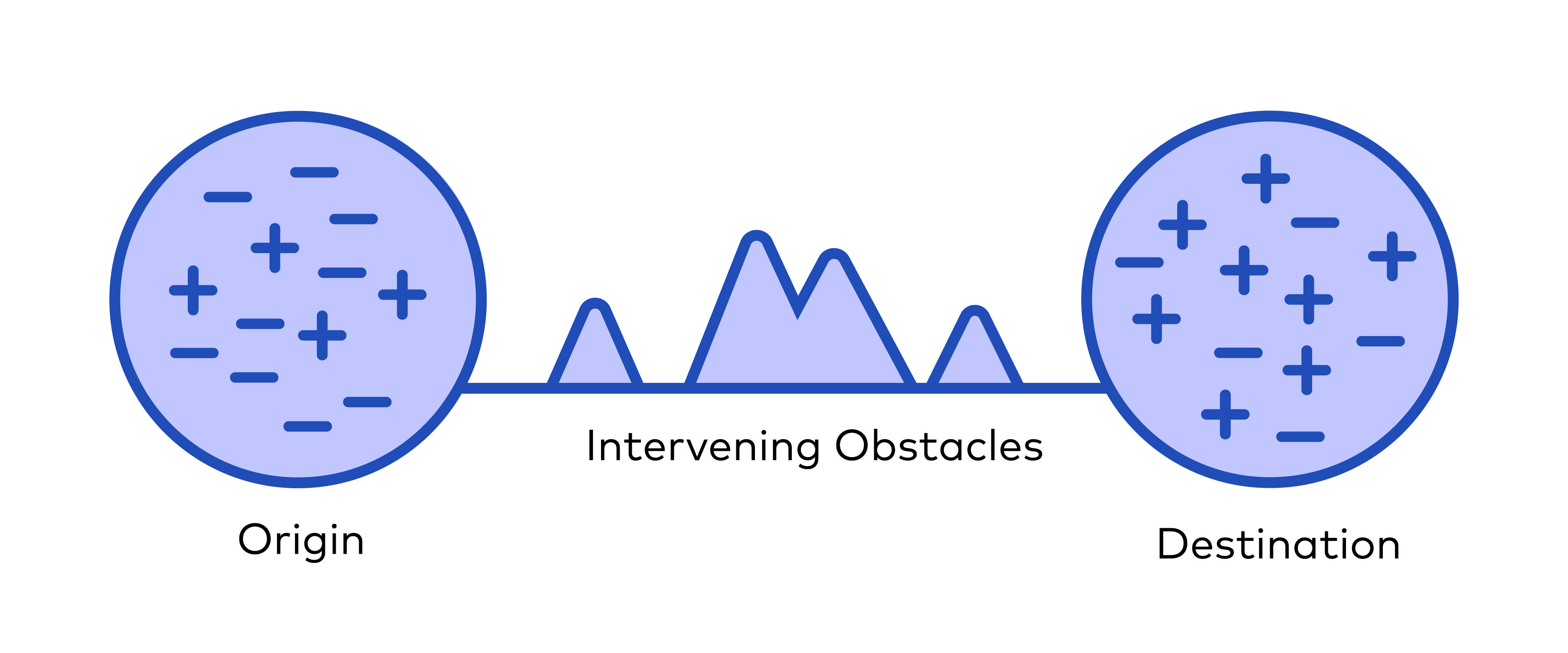

The Push and Pull-model

A common approach in migration studies is to divide the drivers for migration into push and pull effects (Lee, 1966). The push and pull model refers to the drivers pushing individuals away from a region and the drivers pulling an individual towards a region. Hence, push factors relate to the place of origin, while pull factors pertain to the destination. Examples of pull factors include better job opportunities, higher wages, and natural surroundings that attract migrants. Conversely, limited job prospects, low wages, and high housing costs can push people to leave their current location. Lee (1966) notes that each place has a unique mix of positive and negative factors. Importantly, a place can have both push and pull factors depending on an individual's circumstances and preferences. What one person sees as a positive pull factor (e.g., nightlife and a bustling, noisy environment) may be a push factor for another seeking an escape from the same environment. Figure 1 demonstrates the push and pull factors between place of origin and destination, and the intervening obstacles based on the individual circumstances.

Known migration drivers among young adults

This review explores these migration drivers for young adults, highlighting common push and pull factors between urban and rural areas. Several studies have focused on examining migration drivers of young people, both in international and Nordic contexts (see for example a comprehensive literature review on interregional migration by Etzo,2008). The summary below is based on studies focusing on rural-to-urban migration as well as urban-to-rural migration.

Education opportunities

Many young people, especially in rural areas with limited educational opportunities, pursue higher education by moving. This leads to a common mobility pattern related to university attendance (Rérat, 2014). It also leads to different types of mobility patterns after graduation. For example, those who leave their home region to attend university and stay there, those who attend university in their home region and migrate to another region, those who attend university in a different region than their home region and migrate to a third region, and those who leave their home region to attend university but then return after graduation (Faggian & McCann, 2009). Having migrated before (such as to attend university) is positively associated with spatial openness after graduation (von Proof et al., 2014).

Industrial specialisation, job opportunities & wages

A substantial body of literature identifies jobs and wages as the core motivator for young adult migration (e.g., Öberg, 1995; Hansen & Niedomysl, 2009; Scott, 2010). One of the main points discussed in the literature regarding the pull factors to urban regions has been the availability of more and better job opportunities and higher wages. Urban areas have, to a larger extent than rural areas, been associated with attractive jobs and salaries, and a large and diverse (i.e., a “thick”) labour market (Ahlin et al., 2014). High-skilled job movers are more influenced by pull factors than push factors (Arntz, 2010). Potential income also affects the migration patterns of young adults, where urban centers generally offer higher wages, although certain specialised non-urban regions can also attract labor with higher wage levels (Brixy et al., 2022).

The common mobility behaviour of university graduates is highly dependent on the size and diversity of the regional labour market, which significantly influences the decision to stay or leave a region. A region´s labour market density and diversity can thus be either attractive or unattractive for young career individuals. This is the case for both rural and urban labour markets (Dotti et al., 2013; Venhorst et al., 2011; Krabel & Flöther, 2014). Skill-relatedness theory suggests that workers prefer regions matching their educational background, making it easier to find similar jobs in case of job loss (Rørheim & Boschma, 2022).

Social network

Social networks are influential factors in migration decisions, acting as both push and pull factors. Social ties as motivators for migration include family connections, hometown proximity, past living locations, or familiarity of a home region (Cappellari & Tatsiramos, 2015). These often carry more weight than economic factors, like income (Buenstorf et al., 2016; Dahl & Sorensen, 2010a & 2010b; Lundholm et al., 2004). Thus, social networks serve as pull factors for both urban and rural regions, depending on the individual's background. Kaplan, Grunwald and Hirte (2016) analysed the migration intentions of young knowledge workers in Saxony, Germany. They found that social networks in other cities were strongly associated with the intention of moving whereas having an origin in Saxony was strongly associated with the intention of staying.

Lifestyle migrationLifestyle migration is a concept rather than an isolated determinant associated with migration motivations. The concept includes dimensions of self-identity, favourable economic circumstances and the social capital to holistically address quality of life through migration choices. Lifestyle migration is thus an analytical tool to better understand migration drivers of the relatively more affluent (Benson & O’Reilly, 2016). Lifestyle migration to rural areas involves seeking better housing, family connections, reduced stress, proximity to nature, and increased remote work opportunities. Another important concept is "downshifting," which entails adopting an alternative lifestyle to that of urban life, emphasising work-life balance, improved quality of life, family commitments, environmental concerns, and a calmer everyday life (Sandow & Lundholm 2020; Eimermann et al. 2022; Hoppstadius & Åkerlund, 2022). Depending on the individual’s preferences, lifestyle migration can also be viewed as a pull factor to urban areas. Metropolitan regions are home to a greater supply of diverse cultural and recreational activities, supporting different lifestyle preferences with a higher degree of tolerance and openness which is a common factor associated with urban migration of young adults (Ahlin et al., 2014). Lifestyle migration can be a relevant framework when exploring migration drivers in young adults in the Nordic region, where standards of living are significantly above average on an international scale, combined with a high level of education and a great degree of agency and individual freedom. |

The agglomeration diseconomies: Housing prices & housing shortage

While some agglomeration effects are known to pull people to urban areas, other types of agglomeration effects are associated with negative aspects and can act as push factors from urban areas (Bjerge & Mellander, 2022). These types of negative agglomeration effects are known as “agglomeration diseconomies”. The negative monetary effects of living in large cities, mainly rising property prices and expensive rental markets are major factors pushing young individuals away from urban areas. Research shows that more young adults are leaving urban centres in search of affordable housing (e.g., Buchholz 2022; Sandow & Lundholm 2020). Other common negative factors related to the economic inefficiencies originating from the agglomeration forces include the cost of transport, longer commuting times, and air and noise pollution.

Access to services & leisure opportunities

The quality and availability of services play an important role in place attractiveness. These services include healthcare, educational opportunities, leisure offers and cultural activities. While access to services may not be the sole determinant of migration, it influences migration decisions (Rauhut & Littke, 2016). The body of literature on the creative class (e.g., Florida, 2007) argues that cultural capital in a region impacts the willingness of people to move to a new region.

Return migration

The out-migration of young people from rural areas is significantly driven by educational pursuits and expertise, and as we have discussed, social networks and family ties are strong migration drivers. This group of return migrants is important for rural areas, and encouraging their return is essential for maintaining human capital and shaping the workforce and population (Kotavaara et al., 2018). As von Reichert et al. (2011) phrase it; “return migrants can be a boost to the economic and social vitality of rural communities and that communities should make efforts to both attract and retain them” (p. 35).

Another important group to attract to rural regions is young families with children. Counterurbanisation migration, where these young families leave the urban region and move to a smaller, rural region, can counteract the negative trend of population ageing (Sandow & Lundholm, 2023). Sandow and Lundholm (2020) studied the migration patterns of young families in Sweden, looking at different groups of skilled professionals. They found that, during 2003-2013, a small but steady flow of families from urban areas to more rural/smaller areas were prevalent. Among this group, there was an overrepresentation of highly educated people, creating the potential for an increased inflow of competence and skills in the receiving areas. These new residents, young families with children, form a group that is attractive for rural regions. They can both improve the demographic structure and if they are highly skilled workers, it can boost the local economy (Sandow & Lundholm, 2020).

In their study of counterurbanisation and internal migration among young families with children in Sweden, Sandow and Lundholm (2023) found that a large share of counter-urban movers are former urban movers who decided to return to their home region. The likelihood was also higher if the returnees still had family members living in the home region, showing that family ties are an important factor in counter-urban migration. Grimsrud (2011) investigated the counterurban situation in Norway and found that most movers to rural areas in the country have ties to the area. Either they themselves grew up or had lived there, or it is where their partner grew up.

Hence, rural in-migrants are motivated by family connections. Additionally, Bjerke and Mellander (2017) investigated return migration among university graduates in Sweden and found that those with children were more likely to move back to a rural region when they were finished with their university education.

Hence, rural in-migrants are motivated by family connections. Additionally, Bjerke and Mellander (2017) investigated return migration among university graduates in Sweden and found that those with children were more likely to move back to a rural region when they were finished with their university education.

Mulder et al. (2020a; 2020b) explored young adult’s return migration from large cities in Sweden in connection to family ties. Many young people migrate to cities for education and work opportunities, and the authors found that young adults were more likely to return to their area of origin if they still had siblings or parents living in that region. Family ties play a significant role in attracting young adults back to their home region, Additionally, the study also found that other factors influencing return migration were adverse circumstances (i.e., success-failure dichotomy). In situations such as unemployment, low income and dropping out of university, young adults were more likely to return to their home region.

Gender

Gender is a horizontal, cross-cutting theme in our research as well as all research within the Nordic Thematic Group for Green, Innovative and Resilient Regions (2021 – 2024). The gender dimension is particularly important when analysing migration trends in the urban-rural context, especially for young adults, because of the commonly found shortage of young, educated women in rural areas. This gender imbalance has generally been associated with gender dynamics and hierarchies, which were traditionally more expected in rural settings than urban areas. Furthermore, gender influences educational ambitions, employment opportunities, wages, and social capital, and as such gender influences migration decisions and aspirations too. |

The relationship between gender and migration in the Nordic region has been widely explored, particularly the migration of young women from rural to urban areas, and the surplus of men in rural areas (see for example Dahlström, 1996; Bennike, Faber & Nielsen, 2016). In his study on migration flows from Västernorrland during 2000-2014, Johansson (2016) found that net out-migration of young women was only negative for the cohorts of 18-24 years old whereas return migration occurred for women in the ages of 25-29 and particularly in the ages of 30-34. The 30-39 year-olds are often associated with being in the household-creating ages in the life cycle, where people most commonly have their studies and first career steps behind them, and they enter the phases of marriage, mortgage, and childbearing.

Rauhut and Littke (2016) investigated patterns of outmigration and return migration among young women to and from peripheral/rural areas, focusing on Västernorrland County in northern Sweden. They explored whether the women moved away from the rural area or if they moved to the urban area, exploring a set of push and pull factors. Their findings suggest that migration to and from rural areas is a multidimensional process, where studies, attractive labour markets and lifestyle preferences were important factors why they moved to the urban area. On the other hand, if the young women had strong social networks and connections to Västernorrland, they were more likely to return. However, bad infrastructure and a limited services supply, together with cultural aspects such as norms and values, especially regarding traditional gender roles, were factors causing outmigration and ward off young women to return. The challenge of exploring how gender affects and shapes migration decisions are multidimensional and complex. For example, Jóhannesdóttir et al. (2021) investigated the role of gossip in small rural communities in Iceland and found a positive association between love-life gossip and out-migration intentions, especially for women.

Although, recent migration data indicate that the gender balance in rural areas is improving. In their study, Karpestam and Håkansson (2021) explore this diminishing gender gap between urban and rural areas in Sweden and found that traditional gender norms do not explain them.

Summary

The review of young people's mobility behaviour in the early career stage in the Nordic countries highlights that migration decisions are influenced by a set of various push and pull factors, working simultaneously. It is important to understand the background of the mover, where the behavior of the mover is impacted by educational background and industrial specialisation, geographical origin, gender, income-level and civic status.

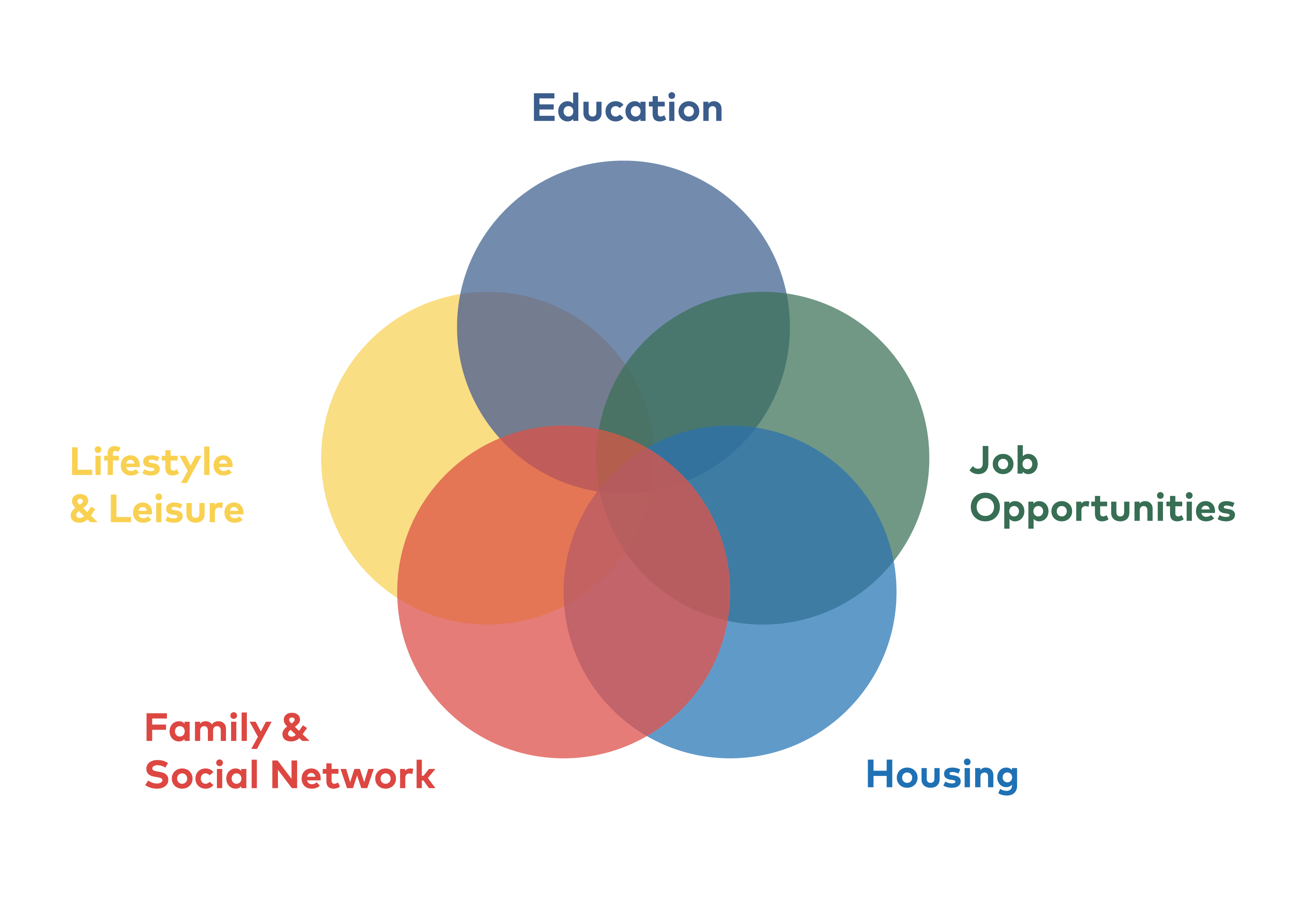

The review indicates the importance of understanding the push and pull factors of the mover. While individual motivations can vary widely, some common factors that have been observed to influence migration decisions in the literature include employment opportunities, quality of life, cultural and lifestyle preferences, family, and social networks, as well as housing and cost of living (illustrated in Figure 2).

Recent migration patterns in the Nordic countries have shown a trend of counter-urban movements; outmigration from urban areas to rural/remote areas (see for example Sandow & Lundholm, 2020 & 2023).

How can this emerging trend be supported and enhanced through regional development policy? How should regional actors prepare and respond to the potential opportunities for positive migration flow to rural and remote areas? To support policymakers in the Nordic region to make the most of these opportunities for regional development, the project will explore the determinants of internal migrants in the Nordic region and seek to identify the motives and drivers of urban to rural migration among young adults.